Haemochromatosis

What is hereditary haemochromatosis?

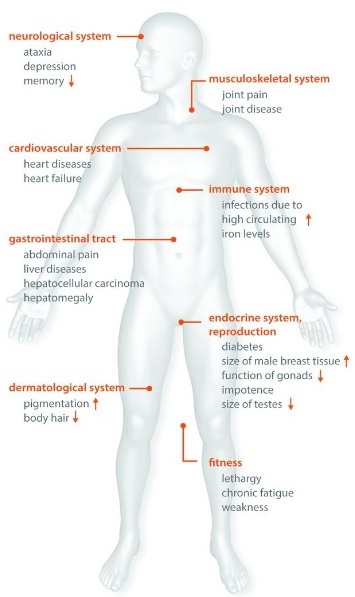

Hereditary haemochromatosis (HH) is a common, inherited condition in which the body absorbs too much iron from food. Over time, this extra iron builds up in the body. If it is not treated, iron overload can damage organs such as the liver, heart, and pancreas.

Iron overload increases the risk of problems such as liver cirrhosis, arthritis, fatigue, and diabetes. Not everyone with the gene develops complications. The chance of illness depends on age, sex, and other factors such as alcohol use and other medical conditions.

The good news is that haemochromatosis is treatable and preventable when it is found early.

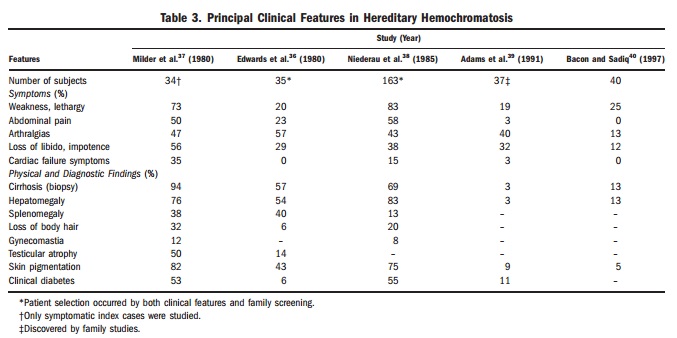

Symptoms of iron overload

Iron overload can cause many non-specific symptoms. These symptoms often develop slowly. Because of this, the condition is easy to miss at first.

Even experienced doctors may not link several mild or vague symptoms to a single cause. Since genetic testing became available, doctors now diagnose haemochromatosis much earlier. Today, many people are diagnosed before they develop complications and sometimes before they notice any symptoms at all.

Testing is especially important if:

-

You have a family member with haemochromatosis, or

-

You are under 50 and have two or more of the symptoms listed below.

Common symptoms and signs

People with haemochromatosis may have one or more of the following:

-

Ongoing fatigue, weakness, or low energy

-

Diabetes (usually later onset)

-

Liver problems (abnormal blood tests, enlarged liver, cirrhosis, or liver cancer)

-

Sexual problems (low sex drive or impotence in men)

-

Absent or irregular periods, or early menopause in women

-

Loss of body hair

-

Heart muscle disease (cardiomyopathy)

-

Abdominal pain, often in the upper right side

-

Joint pain or arthritis, especially in the first and second finger knuckles

-

Memory or mood changes, including irritability or depression

-

Darkening or bronzing of the skin, or a greyish skin tone

The HFE gene and haemochromatosis

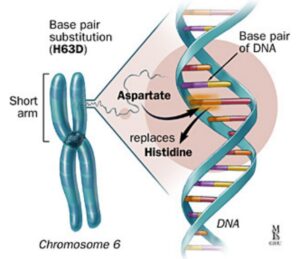

The HFE (high Fe, iron) protein plays an essential role in regulating iron transport into cells. When the HFE gene does not function properly, this regulation fails. Iron then accumulates inside cells and organs over time.

Researchers first identified the HFE gene as the cause of hereditary haemochromatosis in 1996. Since then, genetic testing has become widely available.

HFE-related haemochromatosis is the most common autosomal recessive iron overload disorder in people of Northern European background. About 20% of people carry the H63D variant and about 10% carry the C282Y variant. Most people who carry only one copy of these genes never become unwell.

Two common HFE mutations account for most clinical iron overload. In Australia, over 90% of clinically recognised cases relate to C282Y homozygosity (also called p.Cys282Tyr). Around 5% relate to C282Y/H63D compound heterozygosity (also called p.Cys282Tyr / p.His63Asp).

In populations of Northern European descent:

-

About 0.5% have two C282Y mutations

-

About 2% (roughly 1.7–4.1%) have one C282Y and one H63D mutation

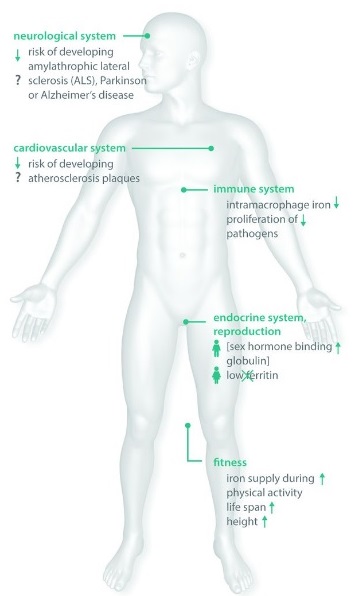

Possible advantages of HFE mutations in asymptomatic individuals

HFE mutations are common, but major disease is much less common. This observation has led to the hypothesis that, over centuries, these variants may have spread because they offered health advantages to carriers.

Several studies suggest that mild increases in iron levels may benefit immune function, general fitness, and reproductive health.

Variants such as C282Y, H63D, and S65C may influence these factors when iron overload remains mild. Some research also reports associations with lower rates of conditions such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and atherosclerosis.

These findings remain associations rather than proven clinical benefits. Ongoing clinical and biochemical research may clarify why HFE mutations persist at such high frequency in some populations.

from Pathophysiological Consequences And Benefits Of HFE Mutations: 20 Years Of Research. Hollerer et al. Haematologica May 2017 102: 809-817

Risk of developing disease

After researchers discovered the HFE gene in 1996, the clinical picture of haemochromatosis changed. At first, many believed that everyone with two abnormal copies of the gene would develop disease. We now know this is not the case.

Although most cases of HFE haemochromatosis in Australia relate to these two common mutations, a positive genetic test only confirms susceptibility, not certainty. Other genetic and environmental factors also influence risk.

Without treatment:

-

People with C282Y homozygosity have a 60–80% lifetime chance of developing abnormal iron indices

-

Only a minority progress through all stages of disease

-

About 28–45% of men

-

About 1–9% of women

-

People with C282Y homozygosity and ferritin below 1000 µg/L, who do not have cirrhosis, diabetes, or heavy alcohol intake, usually have an excellent prognosis, especially with treatment.

One French study suggested that treated C282Y homozygotes had better life expectancy than the background population, although this remains controversial and should not be over-interpreted.

Compound heterozygotes (C282Y / H63D)

Most people with one C282Y and one H63D mutation develop a milder form of disease.

In one large study:

-

Only about 1.3% developed iron overload

-

None developed cirrhosis

Doctors usually diagnose these patients 8–10 years later than C282Y homozygotes. Many also have contributing factors such as obesity (BMI >30 kg/m²) or heavy alcohol intake (>60 g/day for men and >40 g/day for women).

The H63D variant is best viewed as a susceptibility factor. On its own, it usually does not cause disease. Instead, it appears to reduce the liver’s and possibly other organs’ resilience to lifelong environmental stresses and toxins.

Why women are affected less often

Clinical disease occurs much less often in women. Pregnancy and menstruation increase iron loss and delay iron accumulation.

As a result, iron overload in women often appears after menopause.

Genetic counselling and family testing

Doctors should offer genetic counselling to anyone newly diagnosed with haemochromatosis.

First-degree relatives over 20 years old should usually have iron studies (transferrin saturation and ferritin) and HFE genetic testing.

The patient must initiate this process, as they remain the only person legally able to inform family members.

Diagnosis: genes versus disease

Doctors must clearly distinguish between people who carry HFE mutations without symptoms and people who have iron overload with clinical consequences.

Clinicians usually diagnose haemochromatosis at Stage 2 or later, when blood tests show iron overload.

Fasting abnormal iron indices typically include:

-

Transferrin saturation greater than 45%

-

Ferritin above 300 µg/L in men or above 200 µg/L in women

Two caveats matter. Transferrin saturation shows biological and analytical variability, which limits its usefulness as a screening test. Iron levels also vary during the day, and experts still debate the need for fasting samples.

In haemochromatosis, raised transferrin saturation reflects increased iron absorption, while raised ferritin reflects excess iron stores.

Doctors often group ferritin levels as:

-

Mild: less than 500 µg/L

-

Moderate: 500–1000 µg/L

-

Severe: more than 1000 µg/L

Before starting venesection, especially in younger compound heterozygotes, clinicians must exclude other causes of raised ferritin. These include alcohol, dysmetabolic syndrome, liver necrosis, malignancy, inflammation, and infection. Lifestyle change matters when obesity or alcohol excess contributes.

Stages of HFE haemochromatosis

Stage 0: C282Y homozygosity, normal transferrin saturation and ferritin, no symptoms

Stage 1: Transferrin saturation greater than 45%, normal ferritin, no symptoms

Stage 2: Raised transferrin saturation and ferritin, no symptoms

Stage 3: Raised iron indices with symptoms affecting quality of life, such as fatigue, impotence, or arthropathy of the second and third MCP joints

Stage 4: Raised iron indices with organ damage, including cirrhosis with hepatocellular carcinoma risk, insulin-dependent diabetes, and cardiomyopathy

If HFE testing is negative but iron is high

If someone has raised ferritin and transferrin saturation but has one or no HFE mutations, doctors may use:

-

Sequencing of HFE and other known haemochromatosis genes (types 1, 2a/b, 3, and 4), guided by age of onset

-

Liver biopsy showing a hepatic iron index of at least 1.9, and to assess iron distribution and co-existing liver disease

-

Liver MRI in a specialised centre to quantify hepatic iron

-

A trial of therapeutic venesection. If more than 16 units of blood are needed to normalise ferritin, this supports true iron overload. Typical iron removal ranges are 2–6 g for homozygotes and 1.3–2.8 g for compound heterozygotes

Ferritin

Ferritin is the main iron storage protein. Victor Laufberger first isolated it from horse spleen in 1937, and doctors introduced it as a clinical test in the 1970s.

Ferritin allows the body to store iron safely during iron-rich periods and survive iron-poor periods. It also plays roles in iron balance, inflammation, immunity, lipid metabolism, and antioxidant defence. Iron is essential for life, especially for oxygen transport and many cellular processes. In its free form, however, iron is toxic. Ferritin protects cells by binding iron in a non-toxic form.

Ferritin enters the circulation mainly from macrophages and liver cells. Many factors regulate this process, including iron stores, inflammatory cytokines, hormones, and oxidative stress.

Dysmetabolic hyperferritinaemia

Dysmetabolic hyperferritinaemia, also called dysmetabolic hepatosiderosis or insulin resistance–associated iron overload, is a common cause of raised ferritin and is often mistaken for haemochromatosis.

It typically shows:

-

Multiple metabolic abnormalities, including obesity, central adiposity, high blood pressure, atherogenic dyslipidaemia, type 2 diabetes, and hyperuricaemia

-

Raised ferritin, sometimes above 1000 µg/L

-

Normal transferrin saturation below 45% (which may rise if steatohepatitis is present)

-

Mild hepatic iron excess, often less than three times the upper limit of normal on MRI or biopsy

-

Mixed iron deposition in hepatocytes and macrophages on liver biopsy

It can also coexist with haemochromatosis.

Very high ferritin levels

Raised ferritin above 200–500 µg/L is common. In very unwell hospitalised or intensive care patients, ferritin can reach extremely high levels, sometimes between 10,000 and 400,000 µg/L.

When one laboratory reviewed results above 50,000 µg/L, patients usually had several contributing problems. These included renal failure, severe liver injury, infection, blood cancers, inflammatory or rheumatological disease, haemophagocytic syndromes, transfusional iron overload, or haemolytic anaemia.

These causes remain unlikely in most community patients, but they show how complex ferritin interpretation can be.

The iron balancing act

Iron’s ability to carry oxygen and transfer electrons makes it essential for life. The body normally stores about 2–6 g of iron, averaging around 4 g. Most sits in circulating blood, the reticuloendothelial system, muscle myoglobin, and mitochondria.

The average person with haemochromatosis accumulates about 0.5–1 g of iron each year. Symptoms often appear around age 40 in men and around age 60 in women, when total body iron reaches 15–40 g and sometimes exceeds 50 g.

In both iron deficiency and haemochromatosis, 1 ng/mL of ferritin roughly corresponds to 8–10 mg of stored iron, although confidence intervals remain wide. Some people show low ferritin yet still have bone marrow iron. Others show very high ferritin but remain iron deficient. This explains why ferritin always needs expert interpretation.

The body absorbs about 1–2 mg of iron each day, which balances daily losses from skin, gut, and menstruation. Average absorption equals about 10% of dietary intake, but it ranges from 5–35%. Heme iron from meat absorbs much more efficiently than non-heme iron from plants and cereals.

Vitamin C, animal protein, and gastric acid increase non-heme iron absorption. Tea, coffee, calcium, eggs, and strong antacids reduce it.

In haemochromatosis or iron deficiency, absorption can triple. An extra 3 mg per day retained equals about 1 g per year. Over 30 years, that can exceed 30 g of excess iron.

To return total body iron to about 4 g, doctors must remove roughly 26 g of iron. Each unit of blood removes about 250 mg. That means more than 100 units may be needed in severe cases. Weekly removal can take around two years to restore safe iron stores.

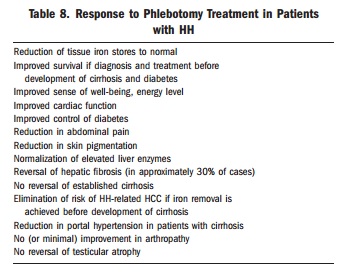

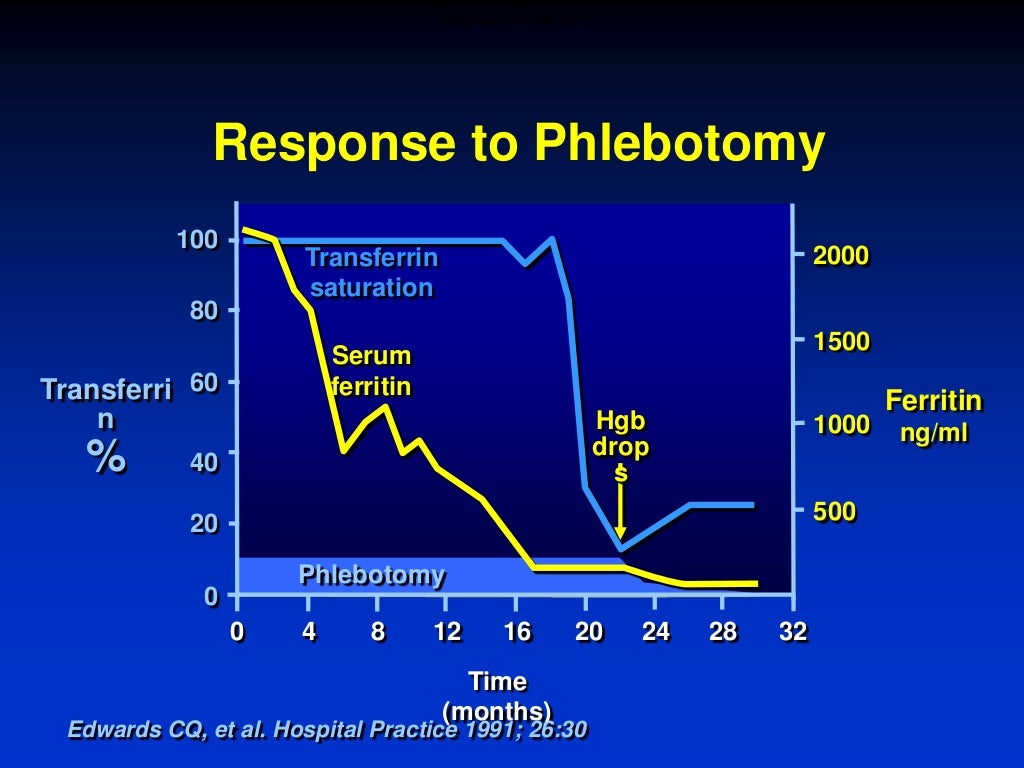

Management of venesection

Induction phase

Doctors usually start venesection at Stage 2 disease, when ferritin rises above about 200–500 µg/L.

A typical approach removes 500 mL once a week if haemoglobin is at least 12 g/dL. Doctors usually repeat iron studies every four weeks.

For very high ferritin, doctors may increase frequency to twice weekly. They adjust volume to body weight, usually around 7 mL/kg, and do not exceed 550 mL per session.

When ferritin falls below 500 µg/L, doctors often reduce frequency to monthly.

The goal is to reach ferritin at or below 50 µg/L at least once. After that, doctors usually maintain ferritin between 25 and 75 µg/L, or below 100 µg/L.

Doctors monitor ferritin every four to six weeks during induction. Once levels approach the target, they often check every two venesections. They assess tolerance clinically and monitor blood pressure. They postpone venesection if haemoglobin falls below 12 g/dL.

Ferritin usually falls by about 30–50 ng/mL with each full unit of blood removed. If ferritin falls faster, inflammation or infection may explain the earlier high level, and the patient may face a risk of over-bleeding.

In the past, many patients needed 80–100 venesections. With earlier diagnosis, many now need 30 or fewer. In one recent series, doctors removed an average of 30 units of blood, which equals about 7.5 g of iron, to normalise body iron stores.

Maintenance phase

Many patients stop treatment once iron levels normalise. This mistake leads to renewed iron accumulation and risk of irreversible organ damage.

For people with haemochromatosis, maintaining iron balance remains a lifelong task. Well-timed blood donation becomes their “medicine.”

After induction, a six-month iron study and haemoglobin test help guide maintenance. Most people need venesection every one to four months, although some need less.

The aim is to keep ferritin at or below 100 µg/L, ideally in the 25–75 µg/L range.

Management relies on ferritin, which reflects stored iron. Doctors do not need to normalise transferrin saturation. Transferrin saturation can fluctuate and remains acceptable as long as it stays below about 75%. Below this level, toxic circulating iron species do not appear.

Doctors usually check ferritin at least every 10 venesections, and then every two as ferritin approaches 100 µg/L. They check haemoglobin within the week before each procedure. Venesection should proceed only if haemoglobin stays above 12 g/dL and haematocrit remains within 20% of the previous value.

Venesections can take place at blood banks, hospitals, day surgery units, general practices, or at home with nursing support, provided a clear plan and shared guidelines exist.

Lifestyle and dietary changes

Reducing liver stress can lower the number of venesections needed. Useful steps include maintaining a healthy weight, exercising regularly, and limiting alcohol.

WHO defines harmful alcohol intake as more than three drinks per day for men or two per day for women. Reducing alcohol matters even more when ferritin exceeds 1000 µg/L or liver tests are abnormal, because this lowers the risk of cirrhosis, liver cancer, and liver failure.

A normal balanced diet usually suffices. People should avoid raw shellfish and limit vitamin C supplements to 200 mg per dose until iron levels normalise. Drinking tea with meals can reduce iron absorption and may reduce venesection needs. Moderate meat intake remains acceptable. Lowering dietary iron intake does not help, because venesection removes far more iron than diet changes can offset.

For more information:

How to Test: HFE related Haemochromatosis

How to Treat: Hereditary