Fibroscan, Liver Elastography, and Non-Invasive Liver Assessments

Liver fibrosis and cirrhosis are the result of chronic liver injury from a range of causes. Careful evaluation of the clinical history, laboratory values, imaging studies, and sometimes liver biopsy remains essential. In most cases, specialists have replaced liver biopsy, the traditional gold standard for assessing liver health, with non-invasive methods:

- Estimating liver stiffness or tissue elasticity by measuring shear wave propagation speed (cs)

- Applying blood enzyme and protein levels into fibrosis scores

Liver Biopsy: Strengths and Limitations

Liver biopsy remains the imperfect but important gold standard for diagnosing liver disease and staging fibrosis. Its strength lies in its long-established history and the diversity of findings in one test. Without it, things are not always as they seem. It provides essential information where:

- The cause of liver abnormalities is unclear. For example, a patient with diabetes, obesity, and abnormal liver enzymes may have autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) or an overlap of AIH and steatohepatitis. A treated AIH patient with persistent enzyme elevation may have inadequately treated AIH or may have developed metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) after steroid-induced weight gain.

- Unexpected findings such as granulomatous inflammation, bile duct injury, or venous congestion are possible.

- Measurement of tissue metal content (e.g., hemochromatosis, Wilson’s disease) is required.

However, biopsy is invasive and carries non-trivial risks, including:

- Pain, hypotension

- Haemorrhage

- Injury to adjacent organs (gallbladder, colon, pleura, kidney, pancreas)

- Sampling error: liver biopsies sample only about 1/50,000 of the total liver volume. Even high-quality percutaneous biopsies (~25 mm) misclassify fibrosis stage approximately 25% of the time compared to larger surgical specimens.

Liver Stiffness Measurement (LSM) with Elastography

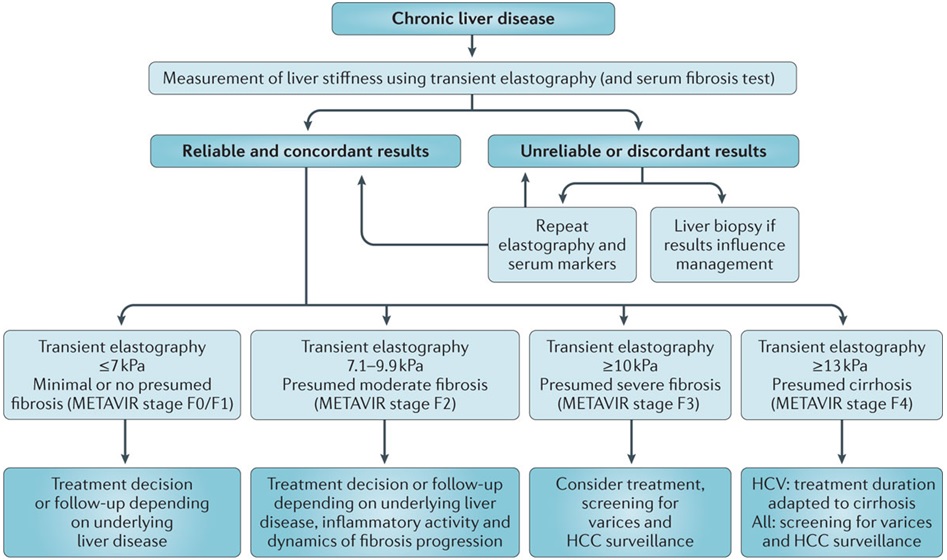

The stiffness of your liver can be measured non-invasively with elastography. This is most commonly done at the time of a routine liver ultrasound using shear wave elastography (SWE). In specialist practice, transient elastography (TE) or magnetic resonance elastography (MRE) may be used.

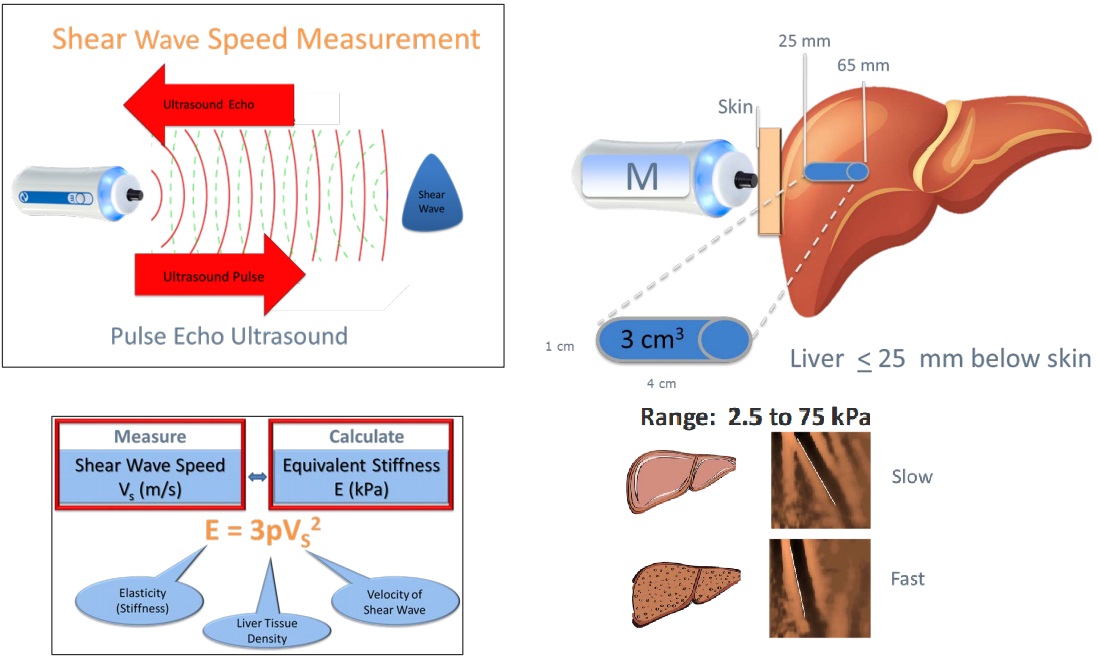

Fibroscan® (Echosens, Paris) uses vibration-controlled transient elastography (VCTE). It was the first commercially available elastography method and remains the technique with the most advanced quality criteria, validation, and evidence base. It is a 10-minute, non-invasive, painless procedure experienced much like a liver ultrasound. A 5 MHz ultrasound transducer probe, mounted on the axis of a vibrator, transmits mild-amplitude, low-frequency vibrations (50 Hz) into the liver tissue, inducing an elastic shear wave that propagates through the underlying tissue. Patients describe the sensation as unusual but not painful — like a gentle flick or tap against the side. The velocity of the wave is directly related to tissue stiffness. The technique measures stiffness in a cylindrical volume approximately 1 cm in diameter and 4 cm in length, amounting to about 1/500 of the entire liver volume — 100 times larger than the volume sampled by a typical liver biopsy.

Shear Wave Elastography (SWE) is the most commonly used method in general radiology practices. SWE is performed as part of a standard ultrasound examination, using acoustic pulses from the ultrasound probe to generate internal shear waves within the liver. Like Fibroscan, SWE measures how fast these waves travel through the liver to estimate stiffness. Patients usually do not feel any sensation during SWE. Although the measurement method differs slightly, SWE provides a reliable and non-invasive way to assess liver health in routine clinical practice. Most radiology practices report liver stiffness using Shear Wave Elastography (SWE), often incorrectly using the brand "Fibroscan". SWE results can vary slightly between machines and software versions, due to differences in calibration and algorithms. Much like bone densitometry (DEXA), it is often impractical to ensure the same machine or software is used over years of follow-up. Fibroscan (TE) remains the most validated and standardised method for liver stiffness assessment. However, SWE shows comparable accuracy at the extremes — particularly when liver stiffness is <7.5 kPa or >9.0 kPa.

Magnetic Resonance Elastography (MRE) uses external vibrations, like TE, to generate mechanical waves through the liver. Specialised MRI sequences then image the propagation of these waves to create a detailed liver stiffness map. It is rarely ordered but MRE provides highly accurate assessment across the whole liver and is particularly useful when ultrasound-based elastography is limited, such as in large or multiple liver cysts/lesions, obesity or ascites.

Important Differences Between SWE and Fibroscan (TE)

| Feature | Shear Wave Elastography (SWE) | Fibroscan (Transient Elastography, TE) |

|---|---|---|

| How shear wave is generated | Acoustic radiation force (ultrasound pulse) | Mechanical external pulse |

| Equipment | Standard ultrasound machine | Dedicated Fibroscan® device |

| Availability | Widely available | Specialist settings |

| Calibration | Machine-specific (some variability) | Highly standardised globally |

| Interpretation thresholds | Slightly higher readings than TE at low fibrosis stages | Standard fibrosis thresholds validated for TE |

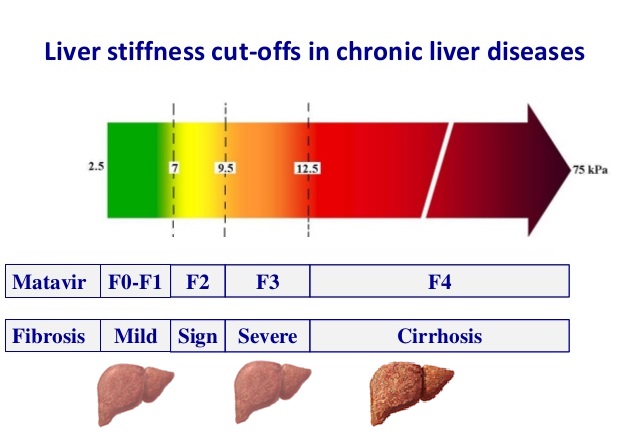

General Interpretation of SWE and Fibroscan (TE) Readings

| SWE (kPa) | TE (kPa) | Interpretation (likely) | Suggested Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| <7.5 | <7.0 | No significant fibrosis | Routine monitoring |

| 7.5–8.0 | 7.0–8.0 | Borderline; mild fibrosis | Consider clinical context |

| >8.0–9.5 | >8.0–9.5 | Suspicious for fibrosis | Recommend confirmation with Fibroscan (TE) |

| >9.5–12.0 | >9.5–12.5 | Significant fibrosis | Fibroscan (TE) or specialist review recommended |

| >12.0 | >12.5 | Advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis | Specialist referral strongly recommended |

Further review may be appropriate when:

-

Rising SWE readings over time, even if liver enzymes remain stable.

-

SWE >7.5 kPa in a patient with:

-

Metabolic risk factors (eg, BMI >30, diabetes, dyslipidaemia).

-

History of alcohol use (>14 standard drinks/week for men; >7 for women).

-

New, persistent, or unexplained elevated liver enzymes:

-

ALT or AST >2 × ULN (Upper Limit of Normal; ULN) where AST 30 U/L (female), 20 U/L (male)).

-

GGT >2 × ULN.

-

-

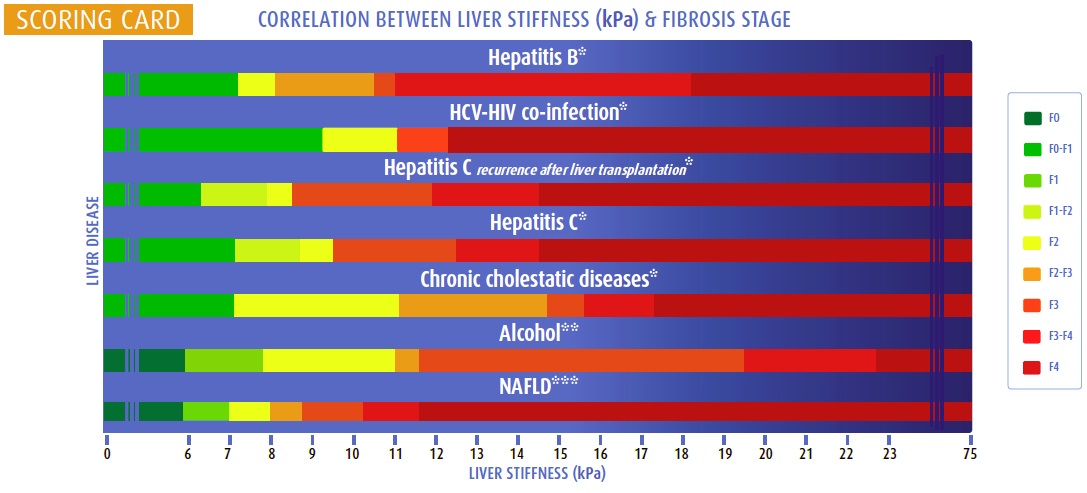

Practical guidance:

The below colour charts refer to Fibroscan (VCTE) not ultrasound Shearwave (SWE). If SWE >8.0 kPa and management decisions depend on accurate fibrosis staging, confirm with Fibroscan (VCTE) where available. When reading SWE reports: Confirm IQR/Median <30%, success rate >60%, and good technical quality comment.

clinically significant portal hypertension (CSPH): VCTE ≤15 kPa + platelets ≥150×109/l rules out CSPH in adults with MASLD; With compensated advanced chronic liver disease, LSM ≥20 kPa or platelets <150×109/l = varices screening/upper GI endoscopy; LSM ≥25 kPa rules in CSPH in non-obese (BMI <30 kg/m2) adults with MASLD; while obesity confounds LSM, no optimal non-invasive test to rule in CSPH in MASLD+obesity

Liver Scores and Biomarkers

Blood-based scores improve fibrosis assessment, especially when combined with elastography:

- APRI (AST to Platelet Ratio Index)

- FIB-4 (Age, AST, ALT, platelets)

- ELF (Enhanced Liver Fibrosis Score: TIMP-1, PIIINP, HA)

- FibroTest (α2-macroglobulin, haptoglobin, apolipoprotein A1, bilirubin, GGT)

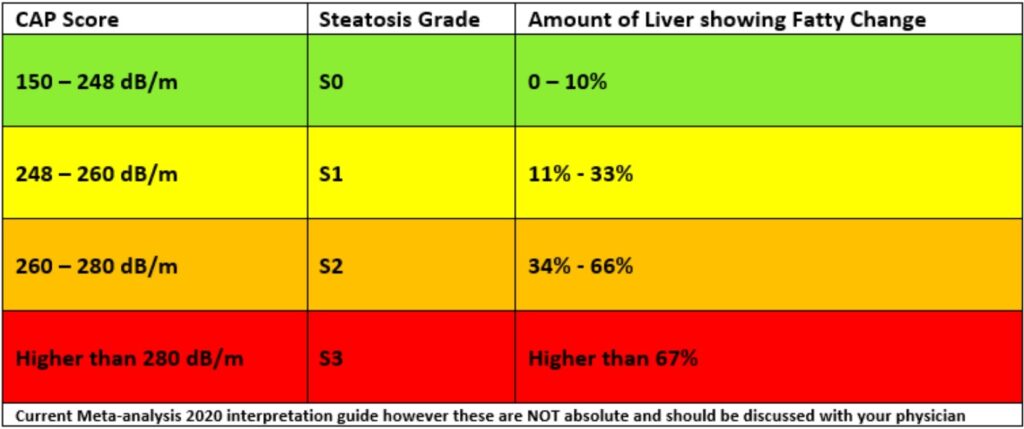

Liver Fat (CAP) Score

Fat accumulation (steatosis) is assessed non-invasively using Fibroscan's Controlled Attenuation Parameter (CAP):

- Measured in decibels per meter (dB/m)

- Scores range from 100 to 400 dB/m

- Higher CAP scores reflect greater degrees of steatosis

Methotrexate (MTX) and Liver Stiffness Monitoring

Methotrexate (MTX) is widely used in inflammatory diseases. Long-term use can lead to hepatic fibrosis, particularly in the presence of additional risk factors such as obesity, diabetes, alcohol use, or pre-existing liver disease. The overall risk of serious liver injury is low.

In modern practice, liver stiffness monitoring with non-invasive methods such as SWE or TE has replaced routine liver biopsy for surveillance. Fibroscan (TE) remains the most validated and standardised method, but SWE provides useful information, particularly when liver stiffness is <7.5 kPa or >9.0 kPa.

Practical Clinical Note

Long-term MTX monitoring:

- LFTs every 3–6 months once stable.

- Baseline viral hepatitis screening and metabolic risk screening

- Elastography every 5 years if cumulative MTX dose > 5 grams and ongoing MTX plan ( SWE ok ;TE if >8 kPA)

- Earlier if red flags appear eg. abnormal LFTs, weight gain, new diabetes, or heavy alcohol use

- Perform an extended liver screen if persistent LFT elevation (>2× ULN) or clinical concern arises.

Routine vs Expanded Liver Screening During Methotrexate Therapy

| Scenario | Tests Recommended |

|---|---|

| Routine Monitoring (stable patient, normal LFTs) |

|

| Expanded Testing (persistent abnormal LFTs, or clinical suspicion) |

|

Summary

- If LFTs are normal and Fibroscan <7.0 kPa → continue routine monitoring (LFTs 3–6 monthly; Fibroscan every 5 years).

- If LFTs are >2× ULN or Fibroscan ≥8.0–9.5 kPa → consider expanded testing and/or hepatology referral.

- Obesity (BMI >30), diabetes, heavy alcohol use (>14/week for men, >7/week for women), or new hepatomegaly on examination/imaging are clinical triggers to lower the threshold for Fibroscan or broader testing.

GP QUICK GUIDE: STEATOTIC LIVER, ABNORMAL LFTs & THE FIB-4 SCORE

Presented by Doug Samuel | 20-minute Update for Primary Care

Approach to Abnormal LFTs

| LFT Pattern | Likely Source | Common Causes |

| ↑ ALT, AST | Hepatocellular | MAFLD, alcohol, hepatitis |

| ↑ ALP, GGT | Cholestatic | Biliary disease, congestions, DILI/ alcohol |

| ↑ Bilirubin | Mixed or obstructive | Late-stage or haemolysis |

| ↓ Albumin / ↑ INR | Liver function | Cirrhosis, acute liver failure |

Always repeat abnormal LFTs + screen:

- ALT Females: 19 ULN, Males: 30 ULN ( despite traditional reference ranges: Male<40, Female<30)

- Hep B/C, iron studies (ferritin, TS), lipids/TG, CRP, HbA1c

- Alcohol history - what did you drink/buy this week?

- Are you taking any natural remedies, herbal or detox products, or supplements for weight loss (green tea extract, Garcinia cambogia), bodybuiding (steroids), anxiety (Kava), or menopause (Black Cohosh)?

- DILI : GP vs hepatologist

- GP safety first, stop common drugs eg. statins, diclofenac vs Ibuprofen/naproxen, paracetamol 2-3g, amoxiclav

- Hepatologist target true hepatotoxins/fibrosis accelerants: methotrexate, amiodarone, valproate, tamoxifen

Fibrosis staging

common system – METAVIR or similar:

F0: No fibrosis

F1: Mild fibrosis (portal)

F2: Moderate fibrosis (periportal or some bridging)

-------------------------------

F3: Advanced fibrosis (bridging fibrosis, but no cirrhosis)

F4: Cirrhosis (extensive scarring and architectural distortion)

-------------------------------

Why it matters:

F3 (advanced fibrosis) is reversible, but carries increased risk of liver-related complications (e.g., progression to cirrhosis, liver failure, portal hypertension, HCC).

Detecting F3 early allows for intervention to halt or reverse disease progression (e.g. through weight loss, metabolic control, avoiding hepatotoxic medications).

Key clinical takeaway: “Advanced fibrosis” = F3 or F4 warrant specialist input, surveillance, and more intensive management.

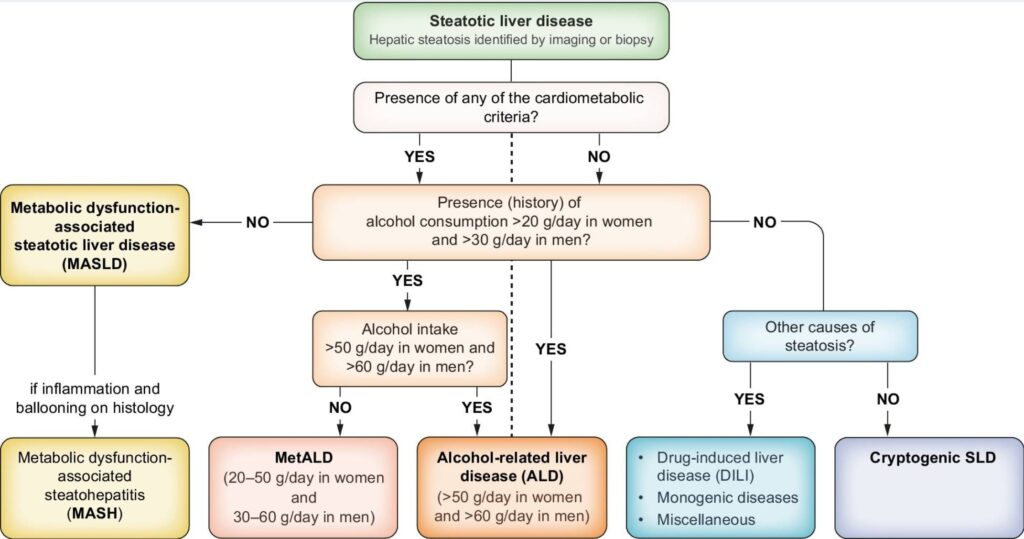

Steatotic Liver Diseases (MAFLD vs ALT vs MetALD vs other)

- Most common cause of abnormal LFTs (>50yo 1 in 2 = MAFLD)

- Often asymptomatic and detected via ALT or imaging

- If obesity, T2DM, metabolic syndrome, central adiposity if BMI 25-30 (F>80cm, M>90-93cm- expire/1/2 point MAL), assume MAFLD, up to 9 in 10, even if LFTs normal

- Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) now known as MASLD to better reflect metabolic etiology and remove stigmatising language

Diagnosis:

- Rule out alcohol, viral hepatitis, medications, haemochromatosis

- Ultrasound confirms steatosis but not fibrosis

- FIB-4 > APRI assesses fibrosis risk (see below)

- Elastography: Shearwave (ultrasound) vs transient (“Fibroscan”)

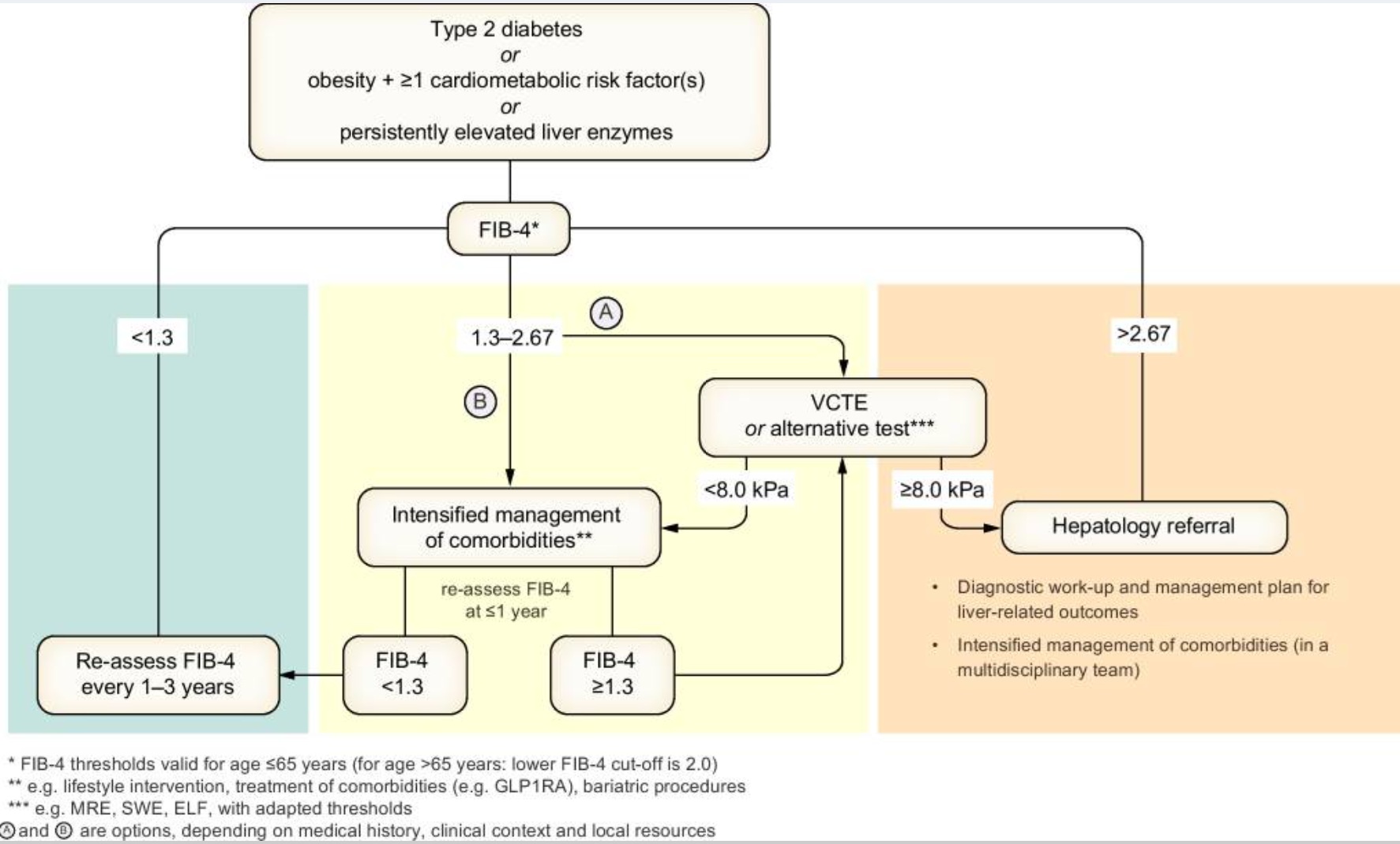

The FIB-4 Score: Fibrosis Risk in NAFLD

Formula:

(Age × AST) / (Platelets × √ALT) [Use online calculator – e.g. MDCalc]

FIB-4 Interpretation (age <65 years):

| FIB-4 Score | Fibrosis Risk | Action |

| <1.3* | Low | GP follow-up, order USS; optimise lifestyle |

| 1.3–2.67 | Intermediate | Order USS/FibroScan ± discuss with hepatology |

| >2.67 | High | Refer to hepatology |

*For age ≥65, <2.0 as the low-risk threshold

false positives: non-hepatic AST>ALT (exercise, meds, alcohol or muscle injury), low platelets (ITP, age), non-liver/fibrosis inflammation (infection/sepsis, autoimmunity, trauma/surgery)

false negatives: age<40, high metabolic burden/silent MASH-F3/4, CRP>5+ferritin>300 (F)/500(M) (ALT <30 F, <40 M - no inflammatory flare), Child's A cirrhosis +/- normal platelets, South+East Asia/Older adults

Summary:

positive predictive value (PPV) of FIB-4 >2.67 for advanced fibrosis (F3/4) varies by population and setting — particularly by prevalence of fibrosis.

| FIB-4 Cutoff | Setting | PPV for F3–4 |

|---|---|---|

| >2.67 | Primary care | ~60–70% |

| >2.67 | hepatology care | ~70–80% |

| >3.25 + Imaging | Combined strategy | ~90%+ |

In Primary Care Settings: PPV of FIB-4 >2.67 for F3/4 fibrosis is typically in the range of 50–70%, depending on population risk.

Lower end (~50%) in general adult screening populations.

Higher end (~70%) in enriched groups (e.g. T2DM, obesity, elevated ALT).

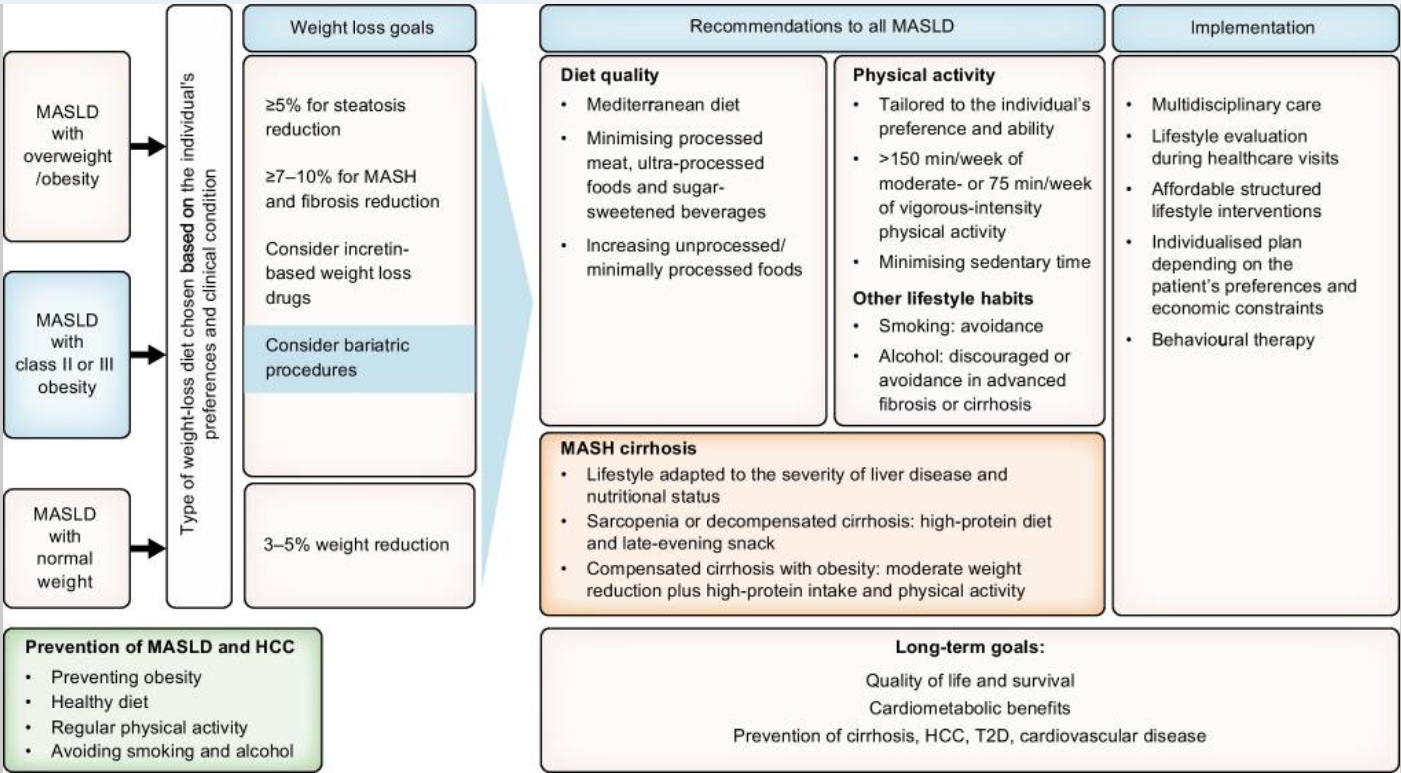

Management Plan in General Practice

First Steps:

- Address metabolic syndrome: weight loss (≥5–10%), diet, exercise

- 5–10% weight reduction = steatohepatitis+fibrosis improves

- >10% weight loss = steatohepatitis resolves in up to 90%

- Optimise diabetes, lipids, BP

- Avoid hepatotoxins (alcohol, excess paracetamol, unnecessary meds/supplements)

- repeat FIB-4 every 12-18 months

- Lifestyle + CVD risk reduction is the cornerstone

Refer if:

- FIB-4 >2.67 or abnormal FibroScan/SWE

- ALT persistently >2x ULN for >6 months (unexplained or higher risk false negative)

- Evidence of fibrosis, cirrhosis, or hepatocellular lesions on imaging or examination

Tips to Remember:

- ALT > AST: Think MAFLD

- AST > ALT (esp >2:1): Think alcohol/fibrosis

- GGT alone ↑: Often benign/metabolic or alcohol

- Always consider cardiovascular risk as top priority in MASLD

- Leading cause of death is cardiovascular in non-cirrhotic

Take home Points on MASLD treatment:

- Focuses on lifestyle modifications: 5% weight loss

- Cardiovascular risk factors should be diligently managed

- Statins should not be withheld or stopped for fear of hepatotoxicity

- Consider if no DM: Vit E and coffee; otherwise: GLP-1 RA

Diagnostic procedures to identify relevant comorbidities of MASLD

| Obesity | BMI |

| Waist circumference | |

| Waist to height ratio | |

| Further investigationsa: | |

| Body composition analysis (if available) | |

| TSH and free thyroxine (if suspicion of hypothyroidism) | |

| Type 2 diabetes or

insulin resistance |

Fasting plasma glucose |

| HbA1c | |

| Oral glucose tolerance test, 2 h post-load glucose | |

| Fasting plasma insulin and/or C-peptide | |

| HOMA-IR | |

| Further investigationsa: | |

| Insulin resistance indices from oral glucose tolerance test or mixed meal tests | |

| Dyslipidaemia | Fasting plasma triglycerides |

| Fasting plasma total, LDL- and HDL-cholesterol | |

| Once in a lifetime: measurement of lipoprotein (a) | |

| Further investigationsa: | |

| Non-esterified fatty acids | |

| Apolipoprotein B | |

| Kidney disease | Creatinine in plasma and urine |

| Albumin in serum and urine | |

| Estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) | |

| Cardiovascular disease | Fasting plasma uric acid |

| Serum high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP) | |

| Serum ferritin | |

| Systolic and diastolic blood pressure | |

| Further investigationsa: | |

| 24 h ambulatory blood pressure monitoring | |

| Echocardiography for heart failure | |

| Serum NT-ProBNP | |

| Transferrin saturation | |

| Atherosclerosis | Complete blood count; Platelets |

| Elevated lipoprotein (a) is an independent causal risk factor for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease | |

| Further investigationsa: | |

| Fibrinogen | |

| Homocysteine | |

| Von Willebrand factor antigen | |

| Carotid artery intima media thickness | |

| EchoDoppler plaque instability | |

| Coronary artery calcification | |

| Obstructive sleep apnoea | Neck circumference |

| Epworth score | |

| Further investigationsa: | |

| Sleep studies | |

| Overnight pulse oximetry | |

| Polisomnography | |

| CPAP trial | |

| PCOS | Sex hormones: LH, FSH, testosterone, SHBG |

| Ovarian ultrasound |

CPAP, continuous positive airway pressure; FSH, follicle-stimulating hormone; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; HOMA-IR, homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; LH, luteinising hormone; NT-ProBNP, N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide; PCOS, polycystic ovary syndrome; SHBG, sex hormone binding globulin; TSH, thyroid-stimulating hormone

aAccording to clinical evaluation and a priori probability

b HOMA-IR = (Fasting Insulin [µU/mL] × Fasting Glucose [mmol/L]) ÷ 22.5

For example, if fasting insulin is 15 µU/mL and fasting glucose is 5.2 mmol/L:

HOMA-IR = (15 × 5.2) ÷ 22.5 = 3.47

-

<2.0: Likely insulin sensitive

-

2.0–2.9: Borderline insulin resistance

-

≥3.0: Insulin resistance likely

(Cutoffs vary slightly by lab and population norms)